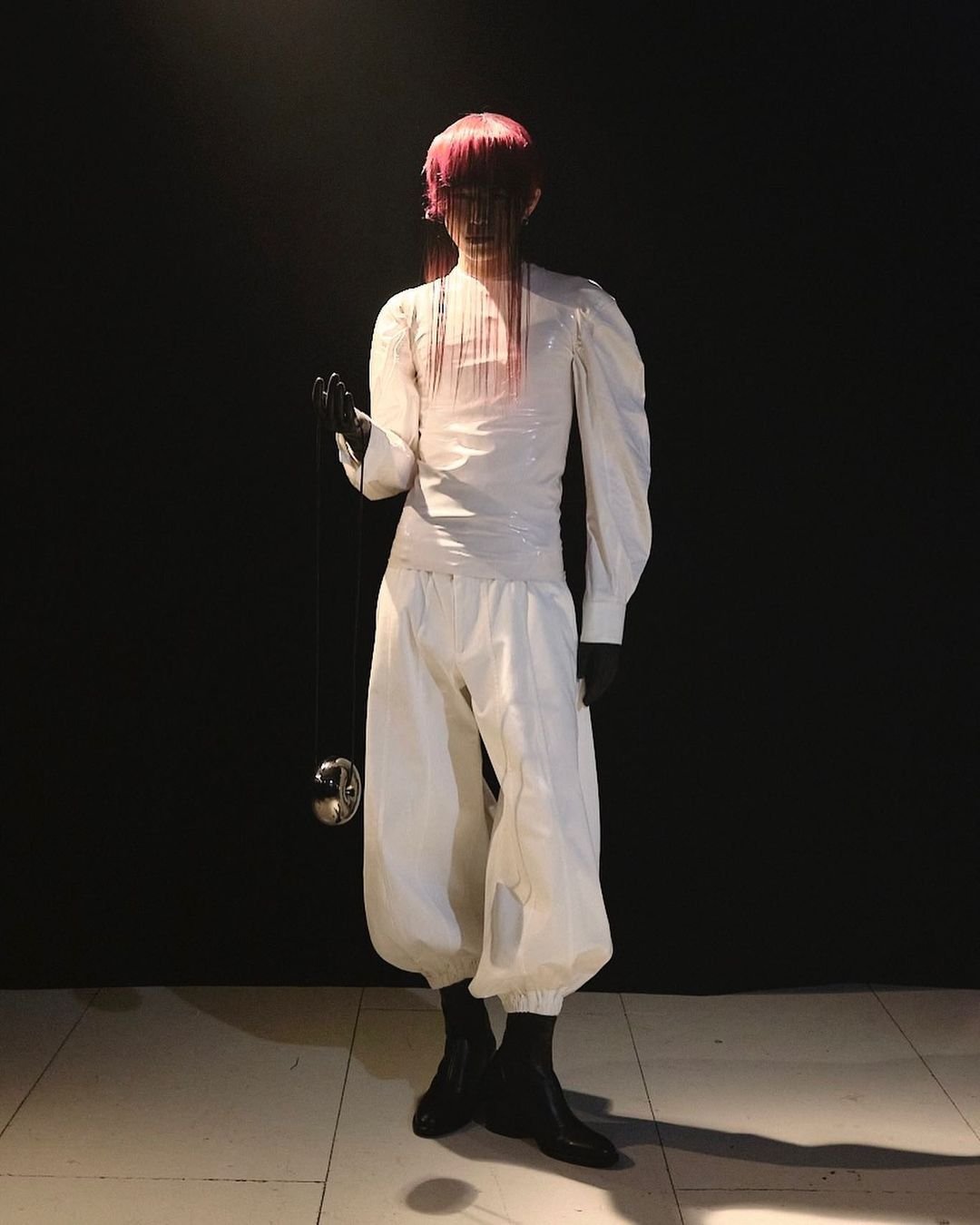

Harikrishnan: Balloon-like proportions

The Indian craftsmen, Harikrishnan, that is combining a dog’s vision, a body builders’ structure and his Indian heritage in providing his boundary pushing designs.

Originally from Kerala, one of India’s southern states, Harikrishnan completed a BA in Fashion Design at the National Institute of Fashion Technology, India, and assisting the 2015 Woolmark Prize Winner, Suket Dhir, in Delhi before enrolling at LCF and now owning his namesake label.

Menswear designer Harikrishnan, set the world alight this year, with his inflatable latex trousers of balloon-like proportions adorned by Sam Smith at the Brit Awards. Hari provided a poignant nod to French photographer Jean-Paul Goude, famous for using the formula ‘Morphing’, a method which exaggerates images by bringing together parts of the same item, taken from different angles.

The biggest media outlets all craving a piece of the Indian native’s work, celebrating the extremes of the human form and delved into how the world appears through another species’ eyes - from the angle, lens, and distortion of the garment. Hari wanted to open up a new outlook on clothing and how to wear them, which he would not have been able to experiment with, when pushing his brand ‘Harri’ commercially.

The trousers that quickly went viral are made from up to 30 individual panels of natural rubber, which allows them to be inflated oversized. Harikrishnan began the process by making three-dimensional clay models. Wielding a latex-base called Supatex for the amplified silhouettes, the trousers were then tack together by grouping individual panels of latex and sticking them together by hand to create horizontal and vertical stripes, supplementing the distorted effect. Once formed, the air was then pumped in through a 7mm inflation valve attached to the bottom in balloon-like proportions.

Here, we speak to Hari about his perception of the human form and how he draws upon connections between his heritage and unique materials in the construction of his garments.

Hey Hari! Thank you for giving us your time. For our readers that do not know who Harikrishnan is, could you just give us an outline of your background from Kerala, India to London, UK. From your childhood growing up in India, to your development in the fashion industry and why you chose this route?

I am a Menswear designer who strives to create a trinity with craft, materiality and imagery. I am 26 yrs old from Kerala, one of the southern states of India. Growing up, I was influenced by my dad's (fine art student back then) life drawing collection and always tried to replicate them. I was very interested in anatomical drawings and body proportions.

In 2012 I went to attend the National Institute of Fashion Technology before working for the 2015 International Woolmark Prize winner Suket Dhir. In 2017 I left the atelier to pursue my Masters in Menswear Design from the London College of Fashion.

I believe that the heart of my practice is materiality.

In the last eight years, I have closely worked with various artists, craft clusters and communities which include weaving schools, wood carving artisans, glassblowing studios, hand-dyeing and lacquer specialists. Currently, my work is about bringing together all these practices collaboratively, exploring their possibilities in the context of Menswear.

Could you talk us through the message you wanted to convey in your brand and your design process in creating garments that at its most simple looks so beautiful and over-dramatic?

My work aims to question the normality of proportions constantly. With that, I believe in pushing the boundaries of fashion imagery in this time of extreme saturation. I aim to create visual imageries capable of forging new perceptions of the human form that's far away from neutrality; to make people question the relevance of the proportions that we see every day.

I usually start off with a vague thought (like my dog's perspective), but then the materiality comes in, and it changes everything completely. For example, I found latex, and that transformed the whole idea because of its unique nature. It is an improvisation that somehow eventually and always comes back to the initial idea, but in a different way than I haven't even imagined.

Did you create your collection as a wearable collection, or is it a deeper underlying message you wanted to convey about the current state of the fashion industry?

I come from a “Ready to Wear'' design background, and during my time in London, I felt that it was limiting me in my thought processes. It took a lot of critical analysis to unlearn things and see clothing beyond just wearability and practicality. Today I approach my practice from an image-making point of view. For me, a collection should have multiple layers which help me connect with others in different ways, each unique telling story. It's a coming together of so many things.

For example, I have hand-carved wooden pieces which carry a rich heritage and a higher level of craftsmanship. For me, wearability is just a part of my practice and body of work.

The process and the narrative is what that matters the most.

I understand that it is quite hard for people to place my work ‒ what do I do with it and do I wear it? I prefer to remain a bit ambiguous. But today a few of my latex pieces are available for purchase on a made to order basis. And I am really excited that something that was meant to be a sculpture became a wearable thing.

How has your Indian heritage influenced your work, and could you outline for us any of your research/design processes in India, which is beautifully prominent in the your most recent collection?

Yes, it has influenced me in many ways. As a South Indian I grew up seeing temples and mythological stories. These figures and imageries were always my fascination. During my time at the National Institute of Fashion Technology, I regularly visited craft communities and worked on projects with them as part of my BA.

My first job gave me a lot of opportunities to work with textile developers and hand-weaving communities, which still informs my design processes significantly.

The beaded vest was a dream project. I have been thinking of collaborating with the community of Channapatna from 2014.

Has your Indian heritage affected your view on the fashion industry and does this give you as a young designer motivation to give new life to waste and dead stock clothing, in an attempt to stop fast fashion brands continuing to take advantage of the East?

Yes, but in a different way. I believe my most significant advantage of being a designer is my awareness about the production processes. Over the last eight years, I have worked with multiple sectors within the industry, exposing myself to all sorts of aspects from production to crafts to merchandising. I have been continuously learning new things, especially from the last four years.

What the people in the west don't know is the complexity of the industry. The only way to slow down Fast fashion is by making people more aware of the production and clothing industry from a grassroots level. Actually, this should start from schools.

Methodologies like waste manipulation or zero waste or dead stock utilisation are just like small fixes which often mislead the consumers, and definitely, brands are taking advantage of this ignorance.

Lastly Hari, who would be the dream brands/ artistic creatives you’d love to collaborate with in order to push your work and message of your brand further?

Tim Walker.